CSIRO science gets new ears

Upgrades at CSIRO’s Parkes radio telescope will now let astronomers ‘hear’ a wider range of radio waves from objects in space.

Upgrades at CSIRO’s Parkes radio telescope will now let astronomers ‘hear’ a wider range of radio waves from objects in space.

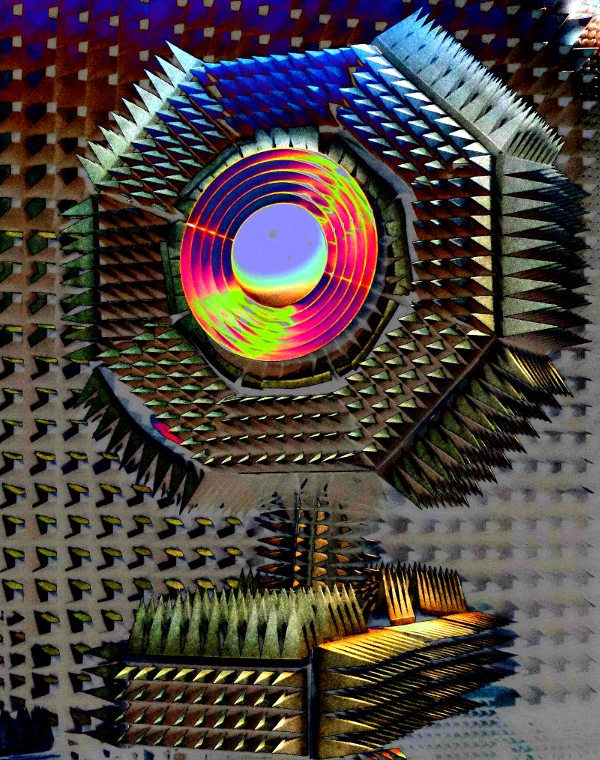

The telescope has been fitted with a receiver, a ‘bionic ear’ for the cosmos that can catch radio waves and turn them into electrical signals for astronomers to analyse.

The $2.5 million instrument was developed by CSIRO and a consortium of Australian universities led by Swinburne University of Technology, with funding from the Australian Research Council, Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy and the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

CSIRO and Swinburne each designed and built parts of the system.

“Stars and galaxies ‘sing’ with different voices, some high, some low,” CSIRO astronomer Dr George Hobbs said.

“It’s like a choir out there.”

A receiver determines which radio frequencies the telescope can hear.

“Until now we’ve had receivers that heard just one part of the choir at a time,” Dr Hobbs said.

“This new one lets us listen to the whole choir at once.”

The new receiver covers a very wide frequency range, 700 MHz to 4 GHz. It does the work of several existing receivers and also covers extra frequencies that they do not.

Parkes has been continually upgraded throughout its lifetime and is already one of the world’s most productive radio telescopes.

The telescope is now 10,000 times more sensitive than when it was built in 1961 and has found most of the known pulsars and most of the ‘fast radio bursts’ that still mystify astronomers.

It also helped reveal the nature of bright sources called quasars and discovered a new spiral arm in our Galaxy.

“Most of the projects the new system will be used for are forefront astronomical science,” Swinburne’s Professor Matthew Bailes, who led the university consortium, said.

Those projects include searching for gravitational waves from black holes in the early Universe, studying the insides of neutron stars, and mapping the magnetic fields that run through our galaxy.

The new receiver will let the telescope do different projects at the same time.

“While some of us are timing a pulsar, other astronomers could be looking for the signs of newborn stars,” Dr Hobbs said.

“The expertise built up in these technologies will enable Australia to compete effectively into the era of the Square Kilometre Array, the world’s largest radio telescope.”

Print

Print