Defect tech tested

A new building assessment tool uses eye-tracking to spot mistakes.

A new building assessment tool uses eye-tracking to spot mistakes.

Building defects account for up to 60 per cent of construction costs, resulting in significant budget blowouts, but new eye-tracking technologies are being developed by the University of South Australia to address the issue.

The technology, embedded in 3D headsets, is designed to help construction workers undertake more thorough checklists and identify building defects early in the construction process, potentially saving companies millions of dollars, time, and resources.

The tool combines building information modelling and eye gaze data captured during a standard building inspection.

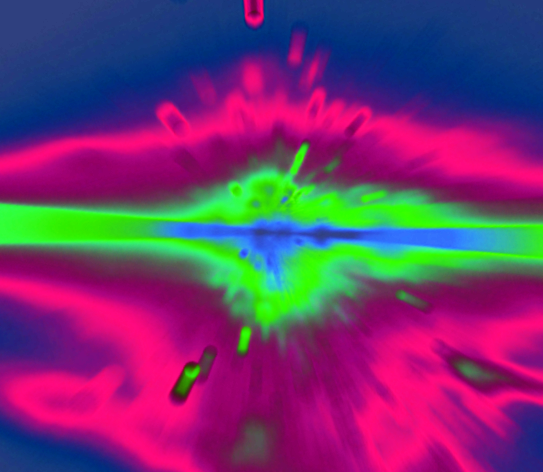

“The augmented reality headsets shoot laser beams out of the bottom of the user’s eye to track where they are looking in a 3D model when they do a building inspection,” says computer scientist Dr James Walsh.

The eye-tracking technology validates the checklist process, ensuring that construction workers are doing a thorough inspection by matching their eye gaze data against the 3D architectural building model.

“The tool ensures that people doing a building inspection are not just walking through a room, but spending enough time to thoroughly check essential elements, identifying that light switches, taps, cables, or pipes are the correct ones and are properly installed,” he said.

“Depending on the nature of the build, whether it’s bespoke or more standardised, the temptation is to tick checklist boxes without doing a rigid inspection, and that can cost thousands of dollars if defects are not picked up early on.”

Dr Walsh says the eye-tracking data does not replace a checklist, but validates it, so defects must still be manually recorded.

“For the construction industry, at the end of the day it’s all about costs and timelines. The earlier we can identify what has gone wrong, the quicker we can fix it and the cheaper it is going to be to remedy it.”

The researchers are working with construction partners to evaluate the tool on site over the life cycle of a building project.

“One of the great things about this project is that it’s an example of how our PhD students and researchers are working on real-world applied problems that can help industry now, not in 10 or 20 years,” Dr Walsh says.

Much of the work was undertaken by University of South Australia PhD student Kieran May.

Print

Print