Gene-editors cut sickle cell code

Researchers in the US have successfully corrected a genetic error in stem cells from patients with sickle cell disease, and then used those cells to grow healthy, mature red blood cells.

Researchers in the US have successfully corrected a genetic error in stem cells from patients with sickle cell disease, and then used those cells to grow healthy, mature red blood cells.

It is an important step in the quest to engineer new body parts.

The team from Johns Hopkins Medicine says it could effectively treat patients with sickle cell disease who need frequent blood transfusions.

The results will be published in an upcoming issue of the journal Stem Cells.

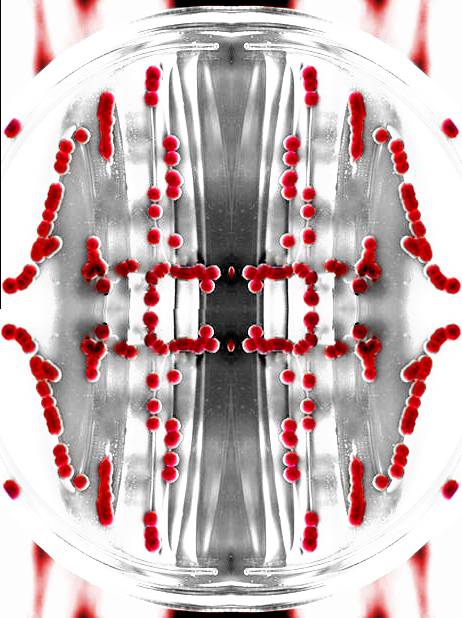

In sickle cell disease, a genetic variation causes blood cells to take on a crescent, or sickle, shape, rather than the typical round shape.

The crescent-shaped cells are sticky and can block blood flow through vessels, often causing great pain and fatigue.

Sometimes, a transplant of blood-producing bone marrow can cure the disease, but many patients either cannot tolerate the transplant procedure, or their transplants fail. For these people, the best option has been to receive regular blood transfusions from healthy donors with matching blood types.

But even this is not a perfect fix, as over time patients' bodies often begin to mount an immune response against the foreign blood.

The solution could be to grow blood cells in the lab that are matched to each patient's own genetic material, and thus could evade the immune system.

A research group led by Professor Linzhao Cheng had already devised a way to use stem cells to make human blood cells. The problem for patients with sickle cell disease is that lab-grown stem cells with their genetic material would have the sickle cell defect.

To solve this problem, the researchers started with patients' blood cells and reprogrammed them into induced pluripotent stem cells, which can make any other cell in the body and grow indefinitely in the laboratory.

They then used an exciting genetic editing technique called CRISPR to snip out the sickle cell gene variant and replace it with the healthy version of the gene.

The final step was to coax the stem cells to grow into mature blood cells. The edited stem cells generated blood cells just as efficiently as stem cells that had not been subjected to CRISPR, the researchers found.

Dr Cheng says that to become medically useful, the technique of growing blood cells from stem cells will have to be made even more efficient and scaled up significantly.

The lab-grown stem cells would also need to be tested for safety.

But, “this study shows it may be possible in the not-too-distant future to provide patients with sickle cell disease with an exciting new treatment option,” he said.

Print

Print