New fibre sets record

Australian engineers have helped cram together 19 cores to make the world’s fastest optical fibre.

Australian engineers have helped cram together 19 cores to make the world’s fastest optical fibre.

The fibre - about the thickness of a human hair - can carry the equivalent of more than 10 million fast home internet connections running at full capacity.

A team of Australian, Japanese, Dutch and Italian researchers set a new speed record for an industry standard optical fibre, achieving 1.7 Petabits over a 67km length of fibre.

The fibre, which contains 19 cores that can each carry a signal, meets the global standards for fibre size ensuring that it can be adopted without massive infrastructure change. It also uses less digital processing, greatly reducing the power required per bit transmitted.

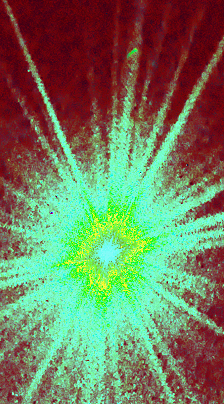

Macquarie University researchers supported the invention by developing a 3D laser-printed glass chip that allows low loss access to the 19 streams of light carried by the fibre and ensures compatibility with existing transmission equipment.

The fibre was developed by the Japanese National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT, Japan) and Sumitomo Electric Industries, Ltd. (SEI, Japan) and the work was performed in collaboration with the Eindhoven University of Technology, University of L’Aquila, and Macquarie University.

All the world’s internet traffic is carried through optical fibres which are each 125 microns thick (comparable to the thickness of a human hair).

These industry standard fibres link continents, data centres, mobile phone towers, satellite ground stations and our homes and businesses.

Back in 1988, the first subsea fibre-optic cable across the Atlantic had a capacity of 20 Megabits or 40,000 telephone calls, in two pairs of fibres. Known as TAT 8, it came just in time to support the development of the World Wide Web, but it was soon at capacity.

The latest generation of subsea cables such as the Grace Hopper cable, which went into service in 2022, carries 22 Terabits in each of 16 fibre pairs.

That is a million times more capacity than TAT 8, but it is still not enough to meet the demand for streaming TV, video conferencing and all our other global communication.

“Decades of optics research around the world has allowed the industry to push more and more data through single fibres,” says Dr Simon Gross from Macquarie University’s School of Engineering.

“They’ve used different colours, different polarisations, light coherence and many other tricks to manipulate light.”

Most current fibres have a single core that carries multiple light signals, limiting the technology to only a few Terabits per second due to interference between the signals.

“We could increase capacity by using thicker fibres. But thicker fibres would be less flexible, more fragile, less suitable for long-haul cables, and would require massive reengineering of optical fibre infrastructure,” says Dr Gross.

“We could just add more fibres. But each fibre adds equipment overhead and cost, and we’d need a lot more fibres.”

To meet the exponentially growing demand for movement of data, telecommunication companies need technologies that offer greater data flow for reduced cost.

The new fibre’s 19 cores can each carry a signal.

“Here at Macquarie University, we’ve created a compact glass chip with a wave guide pattern etched into it by a 3D laser printing technology. It allows feeding of signals into the 19 individual cores of the fibre simultaneously with uniform low losses. Other approaches are lossy and limited in the number of cores,” says Dr Gross.

“It’s been exciting to work with the Japanese leaders in optical fibre technology. I hope we’ll see this technology in subsea cables within five to 10 years.”

Another researcher involved in the experiment, Professor Michael Withford from Macquarie University’s School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, believes this breakthrough in optical fibre technology has far reaching implications.

“The optical chip builds on decades of research into optics at Macquarie University,” says Professor Withford.

“The underlying patented technology has many applications including finding planets orbiting distant stars, disease detection, even identifying damage in sewage pipes.”

The results of this experiment have been published in the proceedings of the 46th Optical Fiber Communication Conference.

Print

Print